|

|

and techniques |

| Swammerdam’s science His life and work Nerve function Muscles Bees and ants "The Bible of Nature" Amazing drawings Techniques and microscopy Preformationism Swammerdam’s life Birth Death A fake “portrait” Science in society Empiricism and religion Mysticism and modern science Illustrations and their meaning Swammerdam in culture Swammerdam's world Friends and contemporaries Contemporary accounts On-line resources Under construction: Discussions of Swammerdam’s work A bibliography of Swammerdam's works Contact |

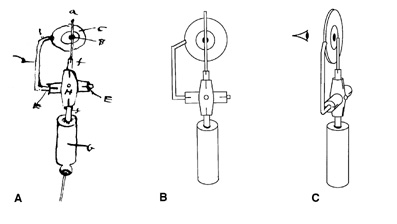

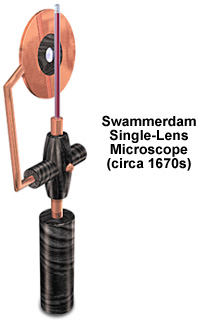

Like many 17th century microscopists, Swammerdam used single-lens microscopes. None of Swammerdam’s microscopes have survived, but we know that he used small bead-lenses (1-2 mm in diameter), some of which he made himself, and which probably had a maximum magnification of around 150x. In March 1678, Swammerdam sent a blood sample to his patron, Melchisedec Thévenot, with a drawing (A) of a microscope that bears a striking resemblance to the microscopes made at the time by Musschenbroek in Leiden. A copy of the drawing is given in (B) and an interpretation of the microscope in use in (C).  Michael W. Davidson subsequently did a 3-D rendering of this drawing for the excellent Molecular Expressions website (click here):  The single-lens microscope is effectively a very small magnifying glass: the object almost touched the lens and the observer had to place their eye close to the lens in order to see the object, and even then it was often difficult to discern anything much. Swammerdam warned the readers of The Book of Nature that the lens “must, for this purpose, be carefully managed, for as it is turned one way or another, different things are seen: one cannot bring the lens nearer, or remove it further, by the least distance, but something is immediately perceived by the sight, which was not observed before.” Swammerdam’s techniques In The Book of Nature, Swammerdam states that he only observed under direct natural light, generally outside on summer mornings, bare-headed to allow the maximum amount of light to reach the lens, “with the sweat pouring down my face”, then writing up his results at night. In a number of letters he explains that he stopped his observations in the autumn and winter, for want of light. His astonishing dissections were carried out with a variety of tools — fine pairs of scissors, a saw made from a small piece of watch spring, a fine sharp-pointed pen-knife, feathers, glass tubes, small tweezers, needles, and forceps — and using a number of original and highly effective techniques to clean the samples, dissolve unwanted tissues, and highlight those of interest. In particular, he developed a method for blowing air down fine glass tubes in order to inflate vessels or to remove tissues, which is still employed in developmental biology laboratories. Swammerdam made all his drawings himself (unlike his great contemporary Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, who employed a number of non-scientific draughtsman), first in red crayon ("sanguine"), then completed in black ink or pencil. Swammerdam recognised that parts of some drawings were not drawn to scale, but as he wrote in The Book of Nature: “Neither need I be uneasy if I have delineated one part somewhat longer, and the other somewhat less; the microscope not admitting of greater accuracy”. The drawings were then copied onto copper plates for printing, a process that Swammerdam, like many contemporary authors, found particularly frustrating; in many of his letters he complains about the cost, accuracy and efficiency of engravers. This page is partly excerpted and adapted from an article that appeared in Endeavour (2000) 24(3) pp122-128. © Elsevier Science, 2000. To download a PDF version of the full article, click here. |